In an interview with Lenny, OpenAI CPO Kevin Weil explains how they designed the UX for their first reasoning model:

"It was the first time that a model needed to sit and think. […] If you asked me something that I needed to think for 20 seconds to answer, what would I do? I wouldn't just go mute and not say anything, and shut down for 20 seconds, and then come back. […] But, you know, if you ask me a hard question, I might go like huh, that's a good question. I might approach it like that, and then think. And you know, sort of give little updates. And that's actually what we ended up shipping."

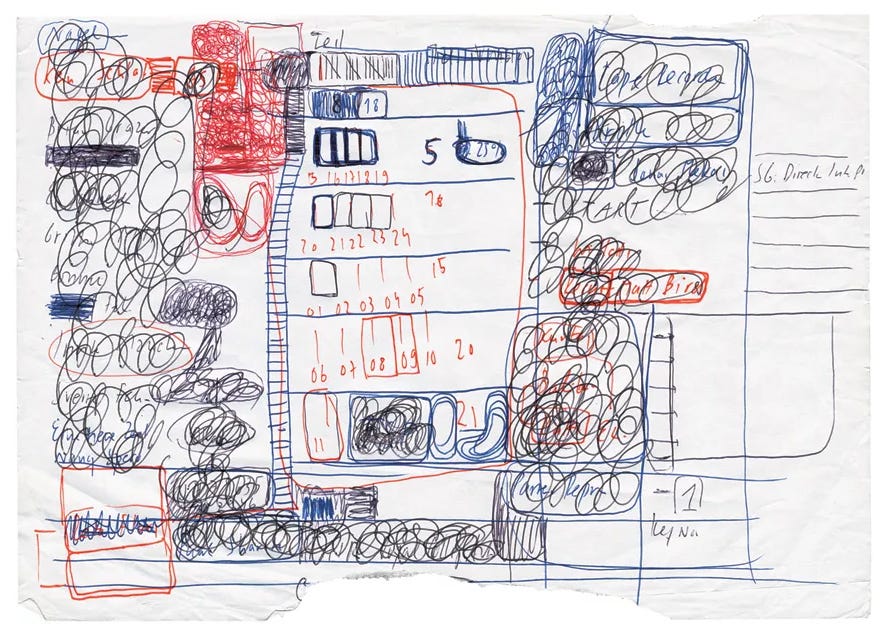

These little insights into the ‘mind’ of ChatGPT (pls don’t take all I say here literally), reminded me of Think Like Clouds, an anthology of notes-to-self from the curator Hans Ulrich Obrist’s archives. The book is essentially a download of Obrist’s chaotic mind featuring notes, sketches, and writing.

After I spent a few hours last weekend going through some of HUO’s pieces again, this lovely tweet popped up on my feed:

Not necessarily a net new observation but very nicely put. I was wondering if maybe there’s more to learn about AI from one of the most influential figures in contemporary art.

What follows is basically a thought bubble that unraveled while I was on the treadmill last night. It might inspire some and bore others.

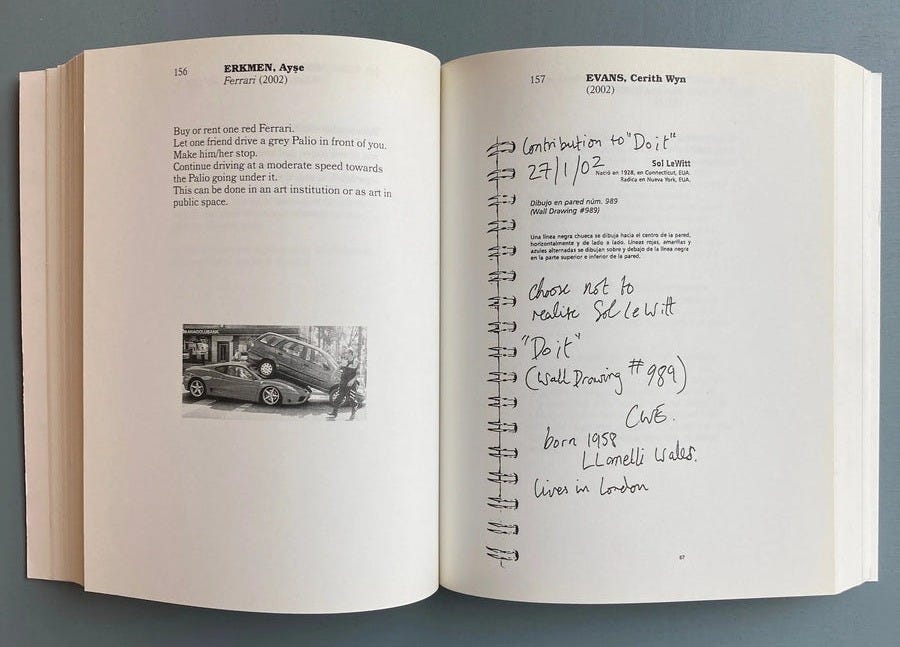

do it is a prompt

In 1993, Hans Ulrich Obrist co-conceived do it, an exhibition with no fixed objects—just instructions. Artists contributed scores to be enacted by others, endlessly reinterpreted across time and place. There were prompts of all length. Some were mega long and technical, others like Yoko Ono’s piece simply read: Listen to the sound of the earth turning.

It was a show built not on presence, but on possibility. Long before chatbots became a thing and prompting a habit, do it anticipated a shift: the work is not the prompt itself, nor the output—it’s what happens in the space between. A prompt is not purely a command. It can be proposition, a provocation, an open score for a system—whether human or machine—to interpret with its own logic, biases, and dreams. And like do it, maybe the results are most alive when they’re misread, mistranslated, or lovingly misused.

Obrist’s curatorial method wasn’t about controlling outcomes. It was about setting conditions. do it didn’t ask for fidelity, but for activation. Each re-interpretation was part of the work’s evolution, not a deviation from it. That’s what today’s AI systems kind of echo in their own way. A prompt doesn’t just retrieve—it initiates. The LLM doesn’t return a single truth, it stages a possibility space where meaning is co-constructed, reshaped by tone, order, and context.

Much like a curator assembling works in a gallery, a prompter doesn’t just input text—they arrange relationships, direct attention, and set the vibe for what might emerge.

thought exhibitions

Obrist described the exhibition not as a container for finished artworks, but as a “form of thinking [in real time].”

To him, exhibitions are not outcomes. They are experiments in attention. Assemblies of unfinished thoughts. Places where meaning is not dictated, but negotiated—between artwork, space, viewer, and context. He once said that every exhibition should contain its own seeds for future exhibitions. In that sense, they are recursive. Self-expanding. Iterative. Like a good prompting session.

LLMs, too, don’t “know” in the traditional sense. They don’t hold fixed truths (LLMs do not contain facts in a retrievable, database-like way). They stage probabilities. They model potential thought paths, then improvise their way forward. The most interesting results often don’t come from precision—they come from tension. When something ambiguous gets fed in and the model surprises you.

That’s not unlike how Obrist curates: not for answers, but for atmospheres of questioning. Think of the LLM as an exhibition space in constant flux. Every prompt is a new configuration of the room. Every regeneration rehangs the work. The user becomes a curator—not selecting discrete pieces, but arranging a condition where something weird might emerge.

just doing things realizing projects

HUO is obsessed with unrealized projects. Can you tell me about your unrealized projects? In this archive of four thousand hours of recorded conversation, it’s the only consistently recurring question. One of his own unrealized projects is not surprisingly an exhibition of unrealized projects.

Some projects are too small to be realized, some are too big, too risky, too expensive. Some of these projects are just intangible ideas or visions, others are better documented.

“We know a lot about architects’ unrealized projects because they obviously publish them all the time, and very often get them built by publishing them. If you think about my dear friend the late Zaha Hadid, at the beginning when she did her utopistic and visionary drawings, everybody in the architecture world thought they were amazing but unbuildable because technology had not yet caught up to these shapes. But of course by publishing these drawings, little by little, she not only imposed her language on the world but also found ways — and technology helped — to will these projects into being. Of course by the end of her life she had dozens of buildings under construction and has realized many of the projects that were once thought to be unrealizable.” - HUO in Flash Art

I think it would be so much fun to revisit the project archive now. Not just as memory, but as input. Honestly, I’d love to see an agent whose sole purpose is to realize unrealized projects—an interface trained not to optimize, but to prototype. One that doesn't ask should we do this?, but simply says let’s try it.

HUO used to have a gigantic postcard collection, something like a personal Bretonesque musée imaginaire, a proto-database, almost a hand-curated latent space. With AI, you no longer have to merely imagine how a combination might look. You can sketch it, stage it, simulate it. A speculative script becomes a short film. A mood board becomes a complete concept. A stray sentence becomes an essay.

The friction between idea and execution—the thing that made so many projects unrealizable—has been radically reduced. It doesn’t mean everything should be made, but it means more things can be. It means intuition can be iterated. Vision can be versioned. Just turn the paintings into postcards (for the time being), and then go bigger.

In a way, I feel like HUO’s entire curatorial practice anticipated this moment: one where the unrealized isn’t lost to the archives, but looped back into the system as seed material. AI doesn’t make us artists or architects—but it does make us faster at building conceptual scaffolding. It turns hesitation into interaction. The sketch into a scene.

What was once a speculative postcard is now a fast render. Maybe the question isn’t what should we build? But rather: what happens when everything becomes prototype-able?

cross-disciplinarity is compute

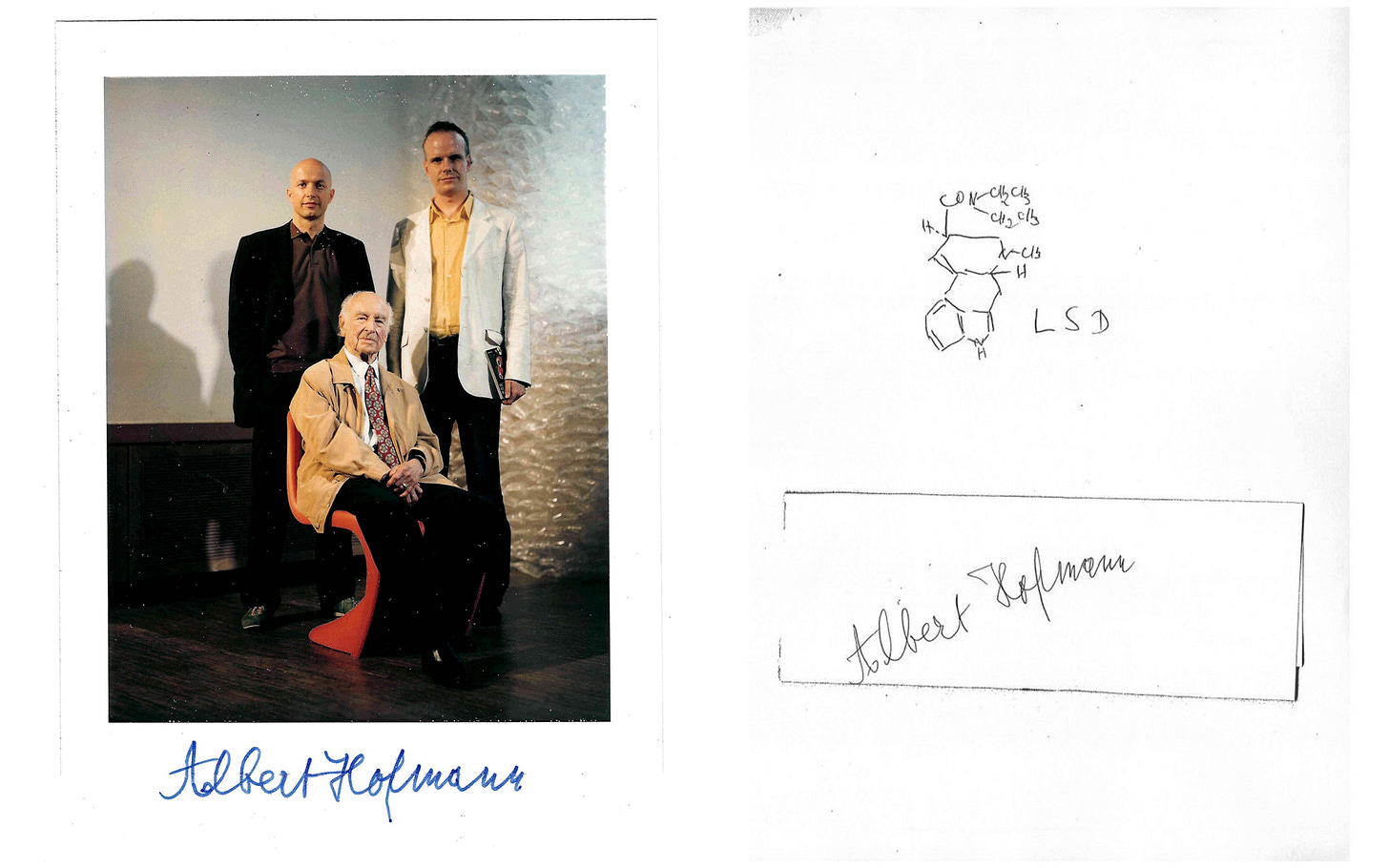

Obrist moves from science to poetry to urbanism without ever asking permission or following restrictive norms. He doesn’t build bridges between categories—he acts like there were never any boundaries.

LLMs are trained on text across domains. They don’t care if it’s API documentation or a line from Clarice Lispector. They don’t even know the difference. That’s what makes them generative. That’s what makes them weird.

This isn’t a bug—it’s a curatorial mode.

It’s also a model for the future of creativity: not monolithic authorship, but sampling, scoring, remixing, situating.

And a model for the future of media: fluid, not bounded, floating from one state to another. Text becomes image becomes video becomes style becomes a poem becomes a song becomes a sound becomes, becomes, becomes, …

GUIs as galleries, agents as exhibitions

If prompting is curating, what’s an interface?

Maybe the interface isn’t just a tool, but a space—a gallery, a stage, a room for thought. A prompt bar is not so different from a white cube wall. What matters isn’t just what appears, but how it appears. In Hans Ulrich Obrist’s world, exhibitions aren’t static—they’re responsive. Environments for staging ideas, not just displaying them.

HUO describes exhibitions as “junctions” or “neural nodes” where artworks and concepts spark off each other. “The exhibition becomes an entity in itself,” he writes. “It’s not just the sum of the parts.” That’s the key: the format changes the thinking. Interfaces—like exhibitions—shape what becomes visible, what stays latent, what gets remixed.

This is exactly what we’re seeing with modern AI agents: a universal agent1 isn’t just an intelligent function—it behaves more like a curated performance of your digital life, shaped by how context is structured, which tools are made available, how memory is managed, and what aspects of its behavior are surfaced or abstracted.

These are curatorial choices: decisions about legibility, agency, and interface that determine how intelligence is staged.

This logic echoes through media theory. McLuhan said, “We shape our tools and thereafter our tools shape us.” HUO’s curatorial approach makes that visible. A room. A pacing. A pairing. Change the space, change the meaning.

We’re already seeing signs of this shift. Long-memory interfaces, evolving personalization layers, and workspace agents all move away from fixed dashboards and toward adaptive environments—interfaces that respond, remember, and reshape themselves around the user’s rhythm.

“I’m interested in formats—formats as a medium,” Obrist once said.

“How can we invent new formats that are like catalysts for thought?”

the memory room: why context is the real ux

Obrist doesn’t wait for the perfect artwork (when I say perfect here, I mean perfected and complete). He begins with a conversation. Often, the work doesn’t even exist yet, but the conditions for it do. That’s probably his strongest curatorial gesture: holding space where something could emerge.

I find this an interesting way to reframe how we interact with AI. Instead of obsessing over use cases, what if we designed for encounters? Spaces that invite meaning to form over time. Less product, more process.

This is where context and memory become essential. Most of the widely known and used models today are technically general-purpose. What makes them feel human, useful, or even magical is the context window they’re given—how much they remember, how they adapt, and how they frame their responses.

Memory isn’t just about recall. It’s about rhythm. Pacing. Continuity. Context isn’t metadata. It’s mood. It’s what lets a system feel intelligent—not because it knows, but because it listens, recalls, maybe misremembers in the right way. When Obrist builds exhibitions, he does so across time. Shows bleed into each other. Interviews span over decades. He doesn’t just collect information—he cultivates continuity. The same goes for the best AI experiences today: they don’t deliver isolated outputs. They create a feeling of thinking together, of co-habiting a timeline. AI isn’t just about accuracy or speed. Maybe it’s about presence.

Not just what the model can do—but what it remembers, forgets, and recontextualizes in the process. A clear use case solves something. But a meaningful context makes you stay with a product.

“[…] Who win memory will unlock retention, defensibility, and the most powerful network effects we’ve seen since social graphs.

Memory, and the deeply personal context that comes with it, will make Facebook Connect’s 2008-era social graph look primitive […]

If Facebook Connect was about who you knew and your surface-level likes, memory is about who you are and the deepest thoughts you carry every day.” - Jeff Morris, The New Moat: Memory

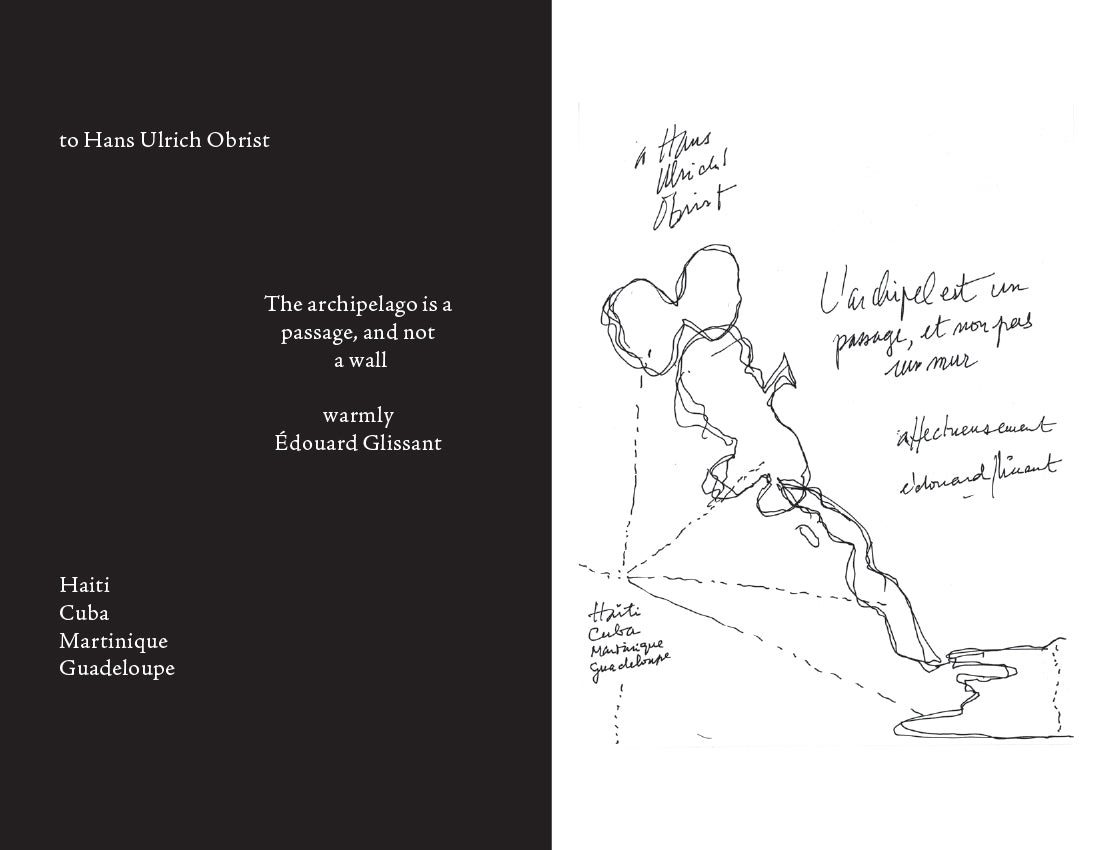

archipelagos

HUO often returns to the work of the writer and philosopher Édouard Glissant.

In Poetics of Relation, Glissant offers the archipelago as a metaphor for a world that resists assimilation, one built on relation, not uniformity. Islands in proximity, not continents in control.

Obrist’s curatorial method mirrors this concept: not central narratives, but constellations. Exhibitions become archipelagos of ideas. Each part is distinct, each encounter is autonomous but resonant with others.

This metaphor feels urgent now, as large language models pull from all domains. A prompt might bridge a tutorial, a tweet, and a line of poetry— in best case to remix them, in worst case to flatten them. Meaning lives in the crossings, not the source.

AI doesn’t have to centralize thought. It can be used to protect difference.

We don’t need AI to smooth everything into sameness.

We need it to hold difference. To keep the edges weird. The references unexpected. The islands intact.

Use it relationally, not reductively.

Otherwise, we slide into slopsciety: a culture of lowest-common-denominator outputs, optimized for engagement but emptied of nuance.

Glissant’s archipelago offers another way.

In the age of AI, the island doesn’t have to disappear.

But only if we insist it stays distinct.

thinking like HUO

I hope you liked this piece. To me, HUO’s constructs and concepts are almost universally applicable, but it felt right (and was fun) to explore this little thought experiment in the context of AI. I generally think he’s an incredibly interesting personality, and I can’t recommend his interviews highly enough. Go read them!

read, read, read

The Art of Conversation [The New Yorker] 🌐

Inside the Mind of Hans Ulrich Obrist [Hypallergic] 🌐

History of the Unrealized [Flash Art] 🌐

An Exhibition Always Hides Another Exhibition [Stern Press] 📓

Do it: The Compendium [Independent Curators International] 📓

By universal agent, I mean an AI system that can operate across tools, contexts, and modalities—a kind of orchestration layer for how we interact with information and software.